|

|

| Route 1 on a busy morning |

We also have a Dunkin Donuts every few miles and one, in particular, that I frequent on my Monday commutes. This palace of pink and creamsicle, which recently relocated a few doors north, had managed to tuck in a drive-through round back, past the dumpster and in between the muffler shop.What struck me was not Dunkin’s ingenuity in getting town permission for what was more an obstacle course than a drive-through, but one lonely little grave that sat in the back corner of their parking lot.

I could not read the memorial, but I could tell by the flags it was a veteran, whom I began to refer to as Private Cruller. Everytime I drove through I checked up on the Private just to be sure he was resting easy. Indeed, Dunkin Donuts did a great job maintaining the site. Nevertheless, it always looked out-of-place back there next to the dumpster.

Last week I was passing by and decided, with Dunkin now officially departed the location, to take a closer look.

|

| The monument is back and right. |

|

| A little closer |

This turns out to be the gravesite of George Washington Flint. A quick check on the Web revealed that George had been born in Peabody, Massachusetts, on 31 October 1846 to Sophronia Lamson Leadbetter (1831-) and Warren Augustus Flint (1822-1884), the second oldest in a family that would one day include eight siblings.

Warren made his living as a cordwainer, or shoemaker. I also learned that George, single and himself a shoemaker, had died 20/23 March 1873 of “congestion of brain” and was buried in “Watertown, Massachusetts then to Lynnfield.” He had served in the Civil War, his headstone inscribed: "George W. Flint, Private, Co. C, Reg. 17" on 25 November 1884.

Before I tell you how 24-year-old George Washington Flint, Civil War veteran (at the age of 16), came to rest in the rear parking lot of a Dunkin Donuts not far from a strip club and an orange dinosaur just off one of the busiest roads in Massachusetts, I want to tell you about a superb essay I read recently by Michael J. Lewis, Professor of Art at Williams College, and given by him at Hillsdale College in March 2012.

Lewis’s essay is entitled The Decline of American Monuments and Memorials and starts by saying that this has been an extraordinary year for American monuments--Ground Zero opened last September in New York, the Martin Luther King Memorial opening in October in Washington, and on tap is the memorial to President Eisenhower. All have been controversial.

The King Memorial, for example, engaged a sculptor from Communist China, used Chinese instead of American granite, misquoted King by using a hypothetical statement, and pictured the civil rights leader not in a great speaking pose (as we might remember him) but looking aloof and, well, despotic, not unlike a Leninist-Maoist memorial.

The proposed Eisenhower Monument will be of a 30-foot, dreamy country boy gazing out upon images of the Kansas prairie. As Lewis says, this is rather unconventional “given that there were millions of dreamy country boys and only one Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe in World War Two.”

Lewis also laments that fact that, in FDR’s memorial, his most effective visual prop--the ubiquitous cigarette holder--was removed by pressure from anti-smoking groups, while the thing he tried hardest to hide in public appearances, his wheelchair, is present. “So the element he flaunted was eliminated,” Lewis says, and “the element he concealed was stressed.”

Professor Lewis reminds us that a monument is supposed to be a “single powerful idea in a single emphatic form, in colossal scale and in permanent materials, made to serve public life.” Open-ended conversations in which various groups bring various interpretations to various forms, Lewis adds, are called schools or museums. He suggests the spontaneous rise of roadside memorials to tragic accidents, a new form of folk art, rely on simple and traditional forms--crosses, handwritten signs, stuffed animals--to tell a powerful story. This is a lesson our modern monument-makers should take to heart: The creators of these roadside memorials “look for widely understood symbols, and they yearn for resolution and closure; they certainly do not aspire to an open-ended process.”

Professor Lewis closes by saying, “For more than a century and a half, we built monuments with spectacular success. We have only been building them badly for a generation. I look at these recent designs, which are perhaps an honest reflection of our divided and uncertain culture, and can’t help but think we can do better once more.”

We decided in 1884, 1893 and again in 1996 that the site was worth preserving. What Professor Lewis said in 2012 about our grand monuments should hold no less true for our smaller memorials: "I can’t help but think we can do better once more."

A Few More Sources

Even if you learned nothing else, you now know that Dunkin Donuts' colors are pink(ie) and creamsicle here.

You may remember that we originally tackled the topic of good and bad statues in 2009 here.

More than you could want to know about Route 1 is here.

Some good history of the Newburyport Turnpike here.

Professor Lewis’s entire lecture, and worth reading, is here.

PIctures of some of the monuments Professor Lewis mentions are here.

The only web source I could find on the George Flint story was here. Further research would no doubt yield more information.

2016 Update: The Hilltop has closed and is gone, the ground along Route 1 awaiting its next venture. I stopped and took these pictures in June 2015.

Warren made his living as a cordwainer, or shoemaker. I also learned that George, single and himself a shoemaker, had died 20/23 March 1873 of “congestion of brain” and was buried in “Watertown, Massachusetts then to Lynnfield.” He had served in the Civil War, his headstone inscribed: "George W. Flint, Private, Co. C, Reg. 17" on 25 November 1884.

|

| With Dunkin Donuts gone only a short time, things aren't looking so great. |

Before I tell you how 24-year-old George Washington Flint, Civil War veteran (at the age of 16), came to rest in the rear parking lot of a Dunkin Donuts not far from a strip club and an orange dinosaur just off one of the busiest roads in Massachusetts, I want to tell you about a superb essay I read recently by Michael J. Lewis, Professor of Art at Williams College, and given by him at Hillsdale College in March 2012.

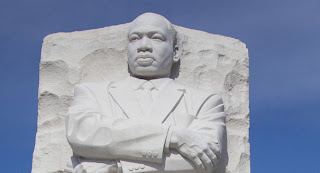

Lewis’s essay is entitled The Decline of American Monuments and Memorials and starts by saying that this has been an extraordinary year for American monuments--Ground Zero opened last September in New York, the Martin Luther King Memorial opening in October in Washington, and on tap is the memorial to President Eisenhower. All have been controversial.

The King Memorial, for example, engaged a sculptor from Communist China, used Chinese instead of American granite, misquoted King by using a hypothetical statement, and pictured the civil rights leader not in a great speaking pose (as we might remember him) but looking aloof and, well, despotic, not unlike a Leninist-Maoist memorial.

|

| The new Martin Luther King Memorial |

The proposed Eisenhower Monument will be of a 30-foot, dreamy country boy gazing out upon images of the Kansas prairie. As Lewis says, this is rather unconventional “given that there were millions of dreamy country boys and only one Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe in World War Two.”

Lewis also laments that fact that, in FDR’s memorial, his most effective visual prop--the ubiquitous cigarette holder--was removed by pressure from anti-smoking groups, while the thing he tried hardest to hide in public appearances, his wheelchair, is present. “So the element he flaunted was eliminated,” Lewis says, and “the element he concealed was stressed.”

Professor Lewis reminds us that a monument is supposed to be a “single powerful idea in a single emphatic form, in colossal scale and in permanent materials, made to serve public life.” Open-ended conversations in which various groups bring various interpretations to various forms, Lewis adds, are called schools or museums. He suggests the spontaneous rise of roadside memorials to tragic accidents, a new form of folk art, rely on simple and traditional forms--crosses, handwritten signs, stuffed animals--to tell a powerful story. This is a lesson our modern monument-makers should take to heart: The creators of these roadside memorials “look for widely understood symbols, and they yearn for resolution and closure; they certainly do not aspire to an open-ended process.”

Professor Lewis closes by saying, “For more than a century and a half, we built monuments with spectacular success. We have only been building them badly for a generation. I look at these recent designs, which are perhaps an honest reflection of our divided and uncertain culture, and can’t help but think we can do better once more.”

George Flint left the army in 1865, suffering from poor health. It's possible he was imprisoned at Andersonville in Georgia, and either there or elsewhere suffered sunstroke in the spring or summer of 1864. This left him with chronic dizzy spells. When he died in Watertown in 1873 he was moved to his parents’ farm in West Peabody along what would have been the Newburyport Turnpike (or present-day Route 1). We might presume that the site of the Dunkin Donuts dumpster was once a quiet wooded setting behind the Flint’s farmhouse, perhaps even the start of a family graveyard. We now know that it was at least nine years, 1884, before George had a proper and fitting memorial--at least in the eyes of his fellow veterans.

|

| Early 20th century Newburyport Turnpike photo--just to get traffic, donuts and dinosaurs out of your mind |

In any event, when Sophronia sold the homestead to a 73-year-old farmer from Maine named J.B. Turner, she also promised to have her son’s remains moved. She was never able to afford this. The Turners apparently allowed veterans to decorate Flint’s grave from time to time, but created a scandal in 1893 when--for whatever reason--Mrs. Turner refused to allow Grand Army of the Republic veterans on her land. The report in the local press described the grave as “rank with weeds and unmarked by stone.” Veterans were angry at “such an outrage on the honored dead, who had suffered the torments of Andersonville and died that his country might live.”

In 1996, with a century of commerce having turned the Newburyport Turnpike into Route 1 and the Flint's farm into a Dunkin Donuts, George Flint's gravesite was again at risk. Four years previously a snowplow had upended the gravestone and some believed it had been deposited in a nearby dumpster.

In October 1996, a group of about fifty people rededicated Flint’s final resting place, a result of the efforts of the Peabody Historic Graveyard Coalition (PHGC) and the support of local businesses. “In a ceremony marked by military honor guards and musket volleys, the sound of a solitary trumpet playing 'Taps' and a rendition of a hymn, Flint’s new marble headstone was unveiled.” Dressed in nineteenth century Union uniforms, members of the Lawrence Light Infantry Honor Guard participated, as well as members of local veterans organizations and the PHGC. Viewing the colorful assemblage of flags and witnessing the ceremony to honor one of his ancestors, was Frank Flint, formerly of Beverly and now residing in Dracut. Dunkin Donuts provided the landscaping for the grave and made a commitment to maintain the site.” A brass plaque was also mounted near the stone.

In 1996, with a century of commerce having turned the Newburyport Turnpike into Route 1 and the Flint's farm into a Dunkin Donuts, George Flint's gravesite was again at risk. Four years previously a snowplow had upended the gravestone and some believed it had been deposited in a nearby dumpster.

In October 1996, a group of about fifty people rededicated Flint’s final resting place, a result of the efforts of the Peabody Historic Graveyard Coalition (PHGC) and the support of local businesses. “In a ceremony marked by military honor guards and musket volleys, the sound of a solitary trumpet playing 'Taps' and a rendition of a hymn, Flint’s new marble headstone was unveiled.” Dressed in nineteenth century Union uniforms, members of the Lawrence Light Infantry Honor Guard participated, as well as members of local veterans organizations and the PHGC. Viewing the colorful assemblage of flags and witnessing the ceremony to honor one of his ancestors, was Frank Flint, formerly of Beverly and now residing in Dracut. Dunkin Donuts provided the landscaping for the grave and made a commitment to maintain the site.” A brass plaque was also mounted near the stone.

So what happens now, I wonder? It’s hard enough for many cities and towns to keep their graveyards maintained, much less a forgotten single stone in the wrong place with scattered family. It would be nice to see it moved to a more appropriate location. It would be easy to see it forgotten. We can only assume that George Washington Flint--like all of us, Professor Lewis says, when we create spontaneous roadside memorials--must “yearn for resolution and closure, and not an open-ended process.”

We decided in 1884, 1893 and again in 1996 that the site was worth preserving. What Professor Lewis said in 2012 about our grand monuments should hold no less true for our smaller memorials: "I can’t help but think we can do better once more."

A Few More Sources

Even if you learned nothing else, you now know that Dunkin Donuts' colors are pink(ie) and creamsicle here.

You may remember that we originally tackled the topic of good and bad statues in 2009 here.

More than you could want to know about Route 1 is here.

Some good history of the Newburyport Turnpike here.

Professor Lewis’s entire lecture, and worth reading, is here.

PIctures of some of the monuments Professor Lewis mentions are here.

The only web source I could find on the George Flint story was here. Further research would no doubt yield more information.

2016 Update: The Hilltop has closed and is gone, the ground along Route 1 awaiting its next venture. I stopped and took these pictures in June 2015.