Other famous rural cemeteries include Mount Hope Cemetery in Bangor (Maine), Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, Albany Rural Cemetery in Menands (New York), Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit and Holly-Wood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Mount Auburn Cemetery covers 175 acres, 98,000 burials, 60,000 monuments, and 9,400 trees and shrubs representing over 1,250 taxa--part living memorial (with 600 burials a year), part history and part renowned arboretum and botanical garden. "Rather than depicting the horror of death," Mount Auburn's literature says, the cemetery's "picturesque landscape. . .was designed to provide solace and comfort to the bereaved and public alike."

The horror of death (and source of an unhealthy local water supply) could be found aplenty in the typical 17th/18th-century urban churchyard cemetery, full of carved skulls and graves dug nearly on top of one another. Here are a few pictures I took in 2009 on a pass-through the King's Chapel Burying Ground on Tremont Street in Boston--precisely the ghoulish congestion Mount Auburn hoped to improve upon.

By comparison, this is what Mount Auburn looked like in its opening decades.

As you can see, there was genius at work.

So, what do you do in a cemetery that is itself a striking innovation, a way of rethinking and re-conceptualizing something as fundamental as death? Of course--look for its entrepreneurs, the folks who spent important moments of their own lives rethinking and re-imagining their worlds.

Take, for example, Nathaniel Bodwitch, a kid from Salem, Massachusetts, who is remembered today as the father of modern maritime navigation. His impact on both his contemporaries and upon us is extraordinary: a book Bodwitch wrote in 1802 is still carried aboard every commissioned U.S. naval vessel.

At the entrance of Mount Auburn is the Story Chapel (below), built in 1898 and named for Mount Auburn's first president, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story.

Nominated to the Court by James Madison, Story remains the youngest Justice at appointment. He was an absolute force on the Marshall Court--including his Amistad opinion made famous by Hollywood--and an early innovator of American jurisprudence. We honor Story today if for nothing else than the many ways in which he reshaped law to protect property rights.

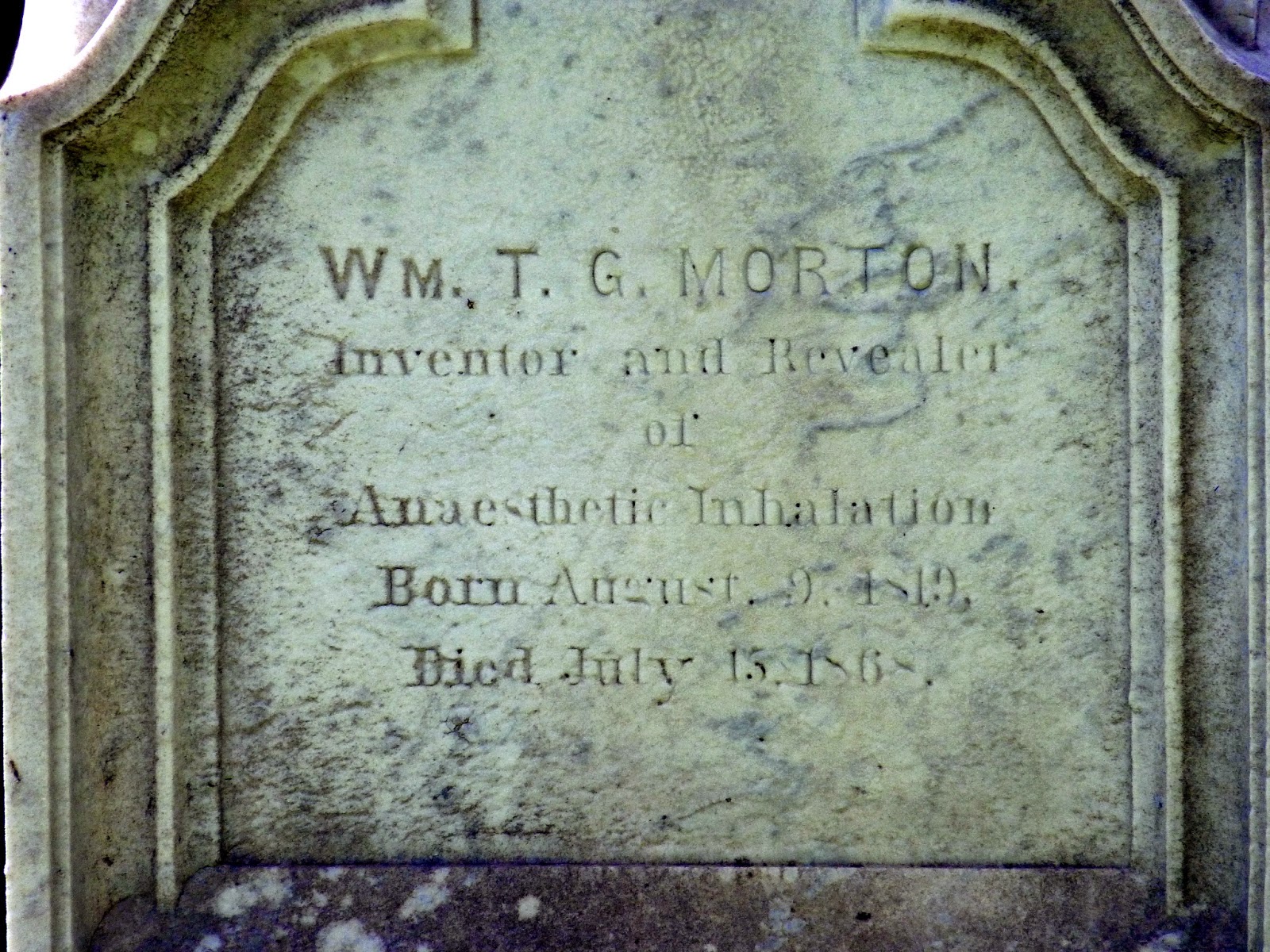

Controversies among inventors and entrepreneurs rage, even into the afterlife. Above is the final resting place of dentist William Morton who, you'll see below, is the "Inventor and Revealer of Anaesthetic Inhalation." In 1846 Morton administered ether and performed the first painless tooth extraction. This led the following year to the use of ether to painlessly remove a tumor from a patient in the operating theater (the still-preserved Ether Dome) of the Massachusetts General Hospital. The medical community, however, was itself pained to learn soon after that Morton had patented "letheon" (known to be ether) and pursued this claim for the rest of his life. If you want the Hollywood version, check out 1944's Paramount picture The Great Moment on Netflix.

Meanwhile, at the other end of Mount Auburn Cemetery rests Charles Thomas Jackson who also claims to have discovered the use of ether. However, Jackson may go down in American entrepreneurial history as the first patent troll: he also claimed prior discovery and sued for invention of guncotton, mining of copper deposits in Lake Superior, and the telegraph. (Samuel Morse was not amused.)

Not all entrepreneurial paternity is in dispute, of course. Below is one of my favorite memorials of the day. Barnabas Bates, a Baptist preacher in Rhode Island and collector at the port of Bristol, was eventually named the Assistant Postmaster of New York. He became an enthusiastic advocate of inexpensive postage and lived to see the 3-cent domestic rate introduced in 1851.

His legacy goes unchallenged, as you'll see below!

Below is a beautiful memorial to Jonas Chickering, one of America's earliest and most famous piano makers. Chickering produced his first 15 pianos in 1823, and 12,000 by the time he died. P.T. Barnum commissioned a Chickering piano to accompany Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, on her concert tour in 1850.

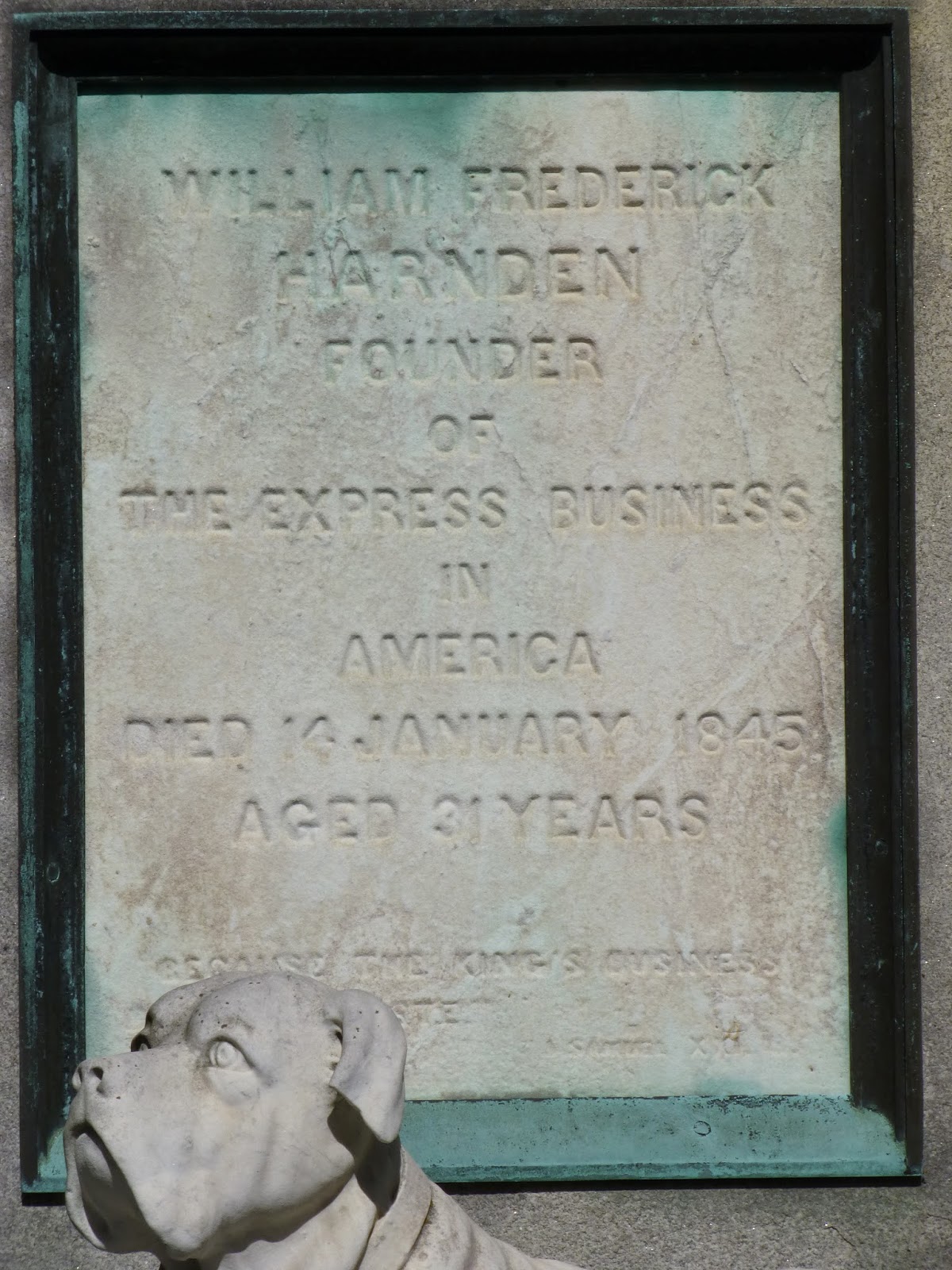

This next memorial was news to me: William Frederick Harnden, "founder of the express business in America."

It turns out that in 1839 Harnden was the first to consign express shipments by rail between Boston and Providence. This business eventually expanded to include New York and transatlantic shipments. While William died young, Harnden and Company lives on today in Adams Express Company, one of oldest companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

I don't have the story on the dog, but will keep looking! (Note the feet on the memorial, too--they look almost like lion paws.)

Mount Auburn also has its share of important social entrepreneurs, including two of the most famous women of the early Republic. Dorothea Dix (being described below by our terrific Mount Auburn guide, Susan) has one of the simplest memorials in the cemetery--masking a rich and complicated life.

Dix worked tirelessly in the 1840s and 50s on behalf of the country's indigent insane, helping create institutions and laws which protected prisoners, the disabled and the mentally ill. Notice the small pebbles placed on top Dix's stone by recent admirers; it's a reminder that places like Mount Auburn do much to connect the living with history.

Another important social entrepreneur prominently featured is Julia Ward Howe, known best as the author of The Battle Hymn of the Republic.

There was much more to her story than the Battle Hymn, however. Howe lived a long, fascinating life as an essayist, poet and playwright; an active abolitionist; and a force in women's suffrage. She was also responsible for Mother's Day. (Her husband, Samuel Gridley Howe, was no slouch, either.)

And last but not least--for this visit, anyway--I discovered at Mount Auburn one of America's modern success stories, Edwin Land, scientist, inventor, entrepreneur and cofounder of Polaroid. Hard as it is to believe, he died almost 25 years ago.

I left a pebble for Dr. (and Mrs.) Land, just so they knew an admirer had paid a visit.

To reinforce the sense of just how far in both distance and sensibilities we've journeyed from the King's Chapel Burying Ground, we need to climb the Washington Tower.

From here you can see back to "the Hub"--Boston being called "the Hub" first by another Mount Auburn guest, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr..

I'll leave you with one more view from Mount Auburn's Washington Tower of another beloved Boston memorial, the CITGO sign high above Fenway Park. At 35-41, 6.5 games out of first place (and not even July 4th), this year's home team may be proof that Mount Auburn is not the only place in town frequented by the living dead.

Who didn't I find? Lots. Katherine Burr Blodgett, who invented "invisible glass" while at GE. Fannie Farmer, who introduced standardized measurements in cooking. Helen B. Taussig, a cardiologist who developed treatment for a common form of "blue baby syndrome." William Barton Rogers, the founder of MIT. Buckminster Fuller. And on and on. And that's just the innovators and entrepreneurs. There's Edwin Booth (John Wilkes' brother), Winslow Homer, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, B.F. Skinner, Arthur Schlesinger and more.

The leaves change color in October. Maybe it'll be a good time to continue the search.

If, of course, I can sneak in a visit around the Red Sox World Series games.