|

| From Wired 1999: Some believed Y2K was the end of technology's Triassic Period. Others knew better. |

Scientists now know that after each of Earth’s mass extinctions, five in all, whatever life survives gets back to work with a vengeance. Biodiversity after cataclysm flourishes.

And so, the Triassic and its archosaurs gave way to the Jurassic Period, when true dinosaurs dominated the land. Tyrannosaurus. The stuff of movies and nightmares. The stuff of endless bedtime books for small children.

Last month I sat down to read Wired magazine, all twelve issues (purchased on eBay) from the year 1999, back-to-back-to-back. I wanted to try to place myself in the world of consumer and office technology just before the turn of the century, and to understand how, and how much, things had changed.

|

| Wired's January 1999 cover |

As I read, I felt like I was visiting a place that I knew, but was just slightly off, like the way a week in the Triassic might have felt to a T-Rex. In 1999, we were celebrating all kinds of colorful technological archosaurs, fascinating creatures with teeth and claws, touch screens and desktop-syncs. But they weren’t yet dinosaurs, and we kind of knew that, too. Biodiversity was flourishing, but many observers understood that we were still short one good extinction before technology’s Jurassic Period could get underway.

Signposts and Stories

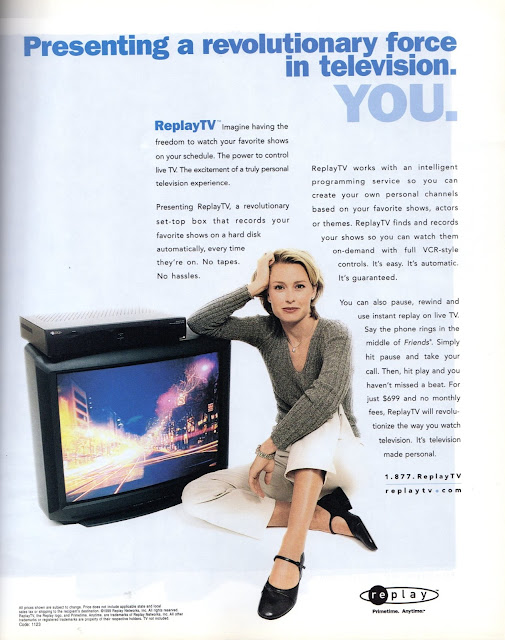

First, some signposts. In 1999, it was still the “Net” and only rarely the “Web.” The entertainment world was television-centric, convinced that disruption of traditional TV was the place where billions of eyeballs would rest in the 21st century.

The world was also email-centric, treating with both admiration and disdain the killer archosaur of the late 20th century. Bill Gates topped the food chain, and it was thought—with everyone likely to become a millionaire in the 21st century—that he would become the world’s first trillionaire. (Ironically, Word still doesn’t recognize that word.) Y2K was in the air, causing some to believe the technological apocalypse was at hand. They were right, of course, but the apocalypse would have nothing to do with a programming glitch.

|

| From Wired's October 1999 issue. All eyes were on the TV. |

The world was also email-centric, treating with both admiration and disdain the killer archosaur of the late 20th century. Bill Gates topped the food chain, and it was thought—with everyone likely to become a millionaire in the 21st century—that he would become the world’s first trillionaire. (Ironically, Word still doesn’t recognize that word.) Y2K was in the air, causing some to believe the technological apocalypse was at hand. They were right, of course, but the apocalypse would have nothing to do with a programming glitch.

|

| From Wired's September 1999 issue. Maybe he'd just give it all away? |

1999 was a time when technology leaders often talked about their own creation stories, that moment when they hacked the first computer their school ever owned, or they became the first on their block to build an Apple I. It was the same way people once talked about the first carburetor they installed, the first automobile engine they rebuilt. In today’s world, where the brightest bulbs were born into a culture of pervasive computing, these stories seem quaint and distant. However, they formed the social construct around which we use technology today, a way of organizing our place in the world, as powerful as family-name and Ivy League school had been in the 1950s. Do you code? Have you founded a technology company? What, you don’t yet drive a Tesla? In 1999, the way of separating the wheat from the chaff was: Were you first on your block to build a computer?

Indeed, the PC ruled in 1999. Dell and HP were churning out beige and grey models while Steve Jobs was offering a more colorful Apple iMac. Jobs had returned to Apple two years earlier and was powering through a reorganization, cutting staff and terminating Newton, Cyberdog, and OpenDoc archosaurs. He was a player, for sure, but still a once-disgraced, niche operator who had yet to ascend to the heights of Olympus he would occupy a decade later.

|

| AltaVista, one of the most promising of all the archosaurs. |

Google had about 60 million indexed pages at the start of 1999 and was being hailed for its technology, but was still ranked by the techno-intelligentsia well behind sites inventing the future like Yahoo! and AOL. Facebook was not yet Facemash, which itself was several years from launch.

However, the one consistent high-flyer from 1999 to the present, from boy wonder to bona fide tech-star, was Jeff Bezos. He had already turned the bookselling world upside down, growing the value of Amazon (still “Amazon.com”) from 503 million at its IPO in 1995 to $22 billion at the start of 1999.

Despite this success, the fact that Bezos wasn’t an engineer—and you can feel the technology pecking order hardening into place--had detractors questioning his wisdom and longevity. Author Chip Bayers writes “Almost since the beginning of Amazon.com’s remarkable rise, Bezos has been characterized as yet another fuzzy-cheeked geek who lucked into an IPO, an uninspired financial technician with a good but not very original idea about distributing goods over the Internet, who would soon be, in the ill-fated phrase of Forrester Research president George Colony, ‘Amazon.toast.’”[1]

|

| Wired, March 1999 |

Despite this success, the fact that Bezos wasn’t an engineer—and you can feel the technology pecking order hardening into place--had detractors questioning his wisdom and longevity. Author Chip Bayers writes “Almost since the beginning of Amazon.com’s remarkable rise, Bezos has been characterized as yet another fuzzy-cheeked geek who lucked into an IPO, an uninspired financial technician with a good but not very original idea about distributing goods over the Internet, who would soon be, in the ill-fated phrase of Forrester Research president George Colony, ‘Amazon.toast.’”[1]

Today, Bezos’ Amazon is worth nearly $500 billion and is selling toast, or at least the bread (along with eggs and bacon, juice and coffee) with which to make a hearty Jurassic breakfast.

In fact, after reading Wired’s 1999 issues, it feels to me like Bezos—more than Gates, Jobs, Zuckerberg, or Page—will be the one archosaur-turned-dinosaur destined to stomp through both the Triassic and Jurrassic technology periods—and perhaps even last into technology’s Cretaceous Era, whatever that might be.

On the flip side, Jim Clark had not yet been forgotten in 1999, and was still lauded as the only person with three billion-dollar start-ups. For whatever reason, he has since faded. The technology equivalent to Clark might be Apple’s Newton, another one-of-a-kind archosaur now barely remembered. Matt Groening, creator of the Simpsons, recalled that he was the first person to buy a Newton “and throw it across the room.”[2]

The Great Archosaurs

The three great archosaurs of the Triassic Era--PC aside--were the Palm Pilot, AOL, and the MP3 player.

3Com’s Palm Pilot was probably the king of all, an electronic organizer introduced in 1996 with the astounding advantage of touch-screen and desktop sync. If the future iPhone would be called the Jesus Phone, then Palm Pilot played the role of John the Baptist, making the way straight.

In 1998 Palm had 77 percent of the market and some 10,000 moonlighting programmers and start-ups focused on building its ecosystem. What they all had in common, author Paul Boutin wrote, was that they “took the first version out of the box and said, ‘Oh, my God. This is it. I want to be part of this.’”[3] (I wrote about my love affair with the Palm here.)

|

| May 1999 (Any idea what "Full leathers for Marilyn" could mean?) |

|

| July 1999 |

|

| November 1999 |

Does this feeling of awestruck community sound familiar?

Palm was under assault in 1999 by a slew of new PDAs from the likes of Casio, Compaq, Handspring, IBM, and Philips running on Microsoft’s Windows CE platform. Hoping to stave off extinction, 3Com responded in 1999 with the Palm VII, a wireless model with Internet connectivity. As disruptive as these wireless data devices were, however, Wired magazine understood that their days were numbered. “While there’s plenty of demand,” the author Jesse Freund noted, “who really needs a gadget that can’t operate for more than few hours continuously, has a tiny grayscale display, and typically costs 25 cents per minute for a 9.6-Kbps connection—with high error rates? Connect. Disconnect. Crash.” Wired gave wireless data devices 24 months, or until 2001.[4]

The first iPhone was released in 2007. Ka-boom.

AOL was another of 1999’s monsters, boasting more than one million dial-up connections. One Wired story titled “Why AOL Always Wins” lauded CEO Steve Case for partnering with Bell Atlantic and its high-speed DSL offering. “No one is better at pushing its product into living rooms,” author Tim Barkow wrote, “and when push comes to shove, America wants its AOL.”[5] In fact, for many Americans, AOL was the Web, ah Net, in 1999.

|

| Four of the "portals" battling with AOL in 1999. From Wired 1999. |

Another fascinating archosaur in 1999 was the MP3 player, a device that compressed music files into manageable sizes that could be easily shared among users. But it wasn’t the only standard in this new Era of the Download; RealNetworks offered a G2 streaming technology and offered a player that handled both G2 and MP3, hoping to vault over competitors like Liquid Audio and a2bmusic, which had developed their own standards. “If God had a jukebox,” author Randall Rothenberg wrote, “it would have every tune ever composed, instantly available anytime. But if the Devil had a studio, he’d make sure those songs were recorded in different formats. . .So far the Web comes off like purgatory.”[6]

|

| Wired's August 1999 cover. A play on another archosaur, MTV. . . |

The iPod launched in October 2001, and the iTunes store two years later. God did have a jukebox, after all. Ka-boom.

Some astute commentators saw that the battle of digital music was just the start of a revolution in all media that would upend radio, television, live music, books, magazines, and Hollywood.

|

| Wired's October 1999 cover. AOL was unstoppable. |

Among the smaller archosaurs of the Triassic Era was the DVD player, first introduced in 1996. By 1999 Sony had unleashed the world’s first five-disc DVD/CD changer, “changing the home entertainment experience.”

Everyone seemed to have individual voicemail by 1999 because everyone still used phones for talking. Terminals began appearing in libraries and airports. TV-commercials hawked products and services all suddenly featuring a website, though some were bold enough to drop the “http://” and other pioneers were even foregoing the “www.” Kevin Poulsen, banned from the Internet as part of his parole conditions for a hacking conviction, desperately tried to recreate the experience his friends were having on-line by “reading the paper, listening to NPR, and watching Headline News all at the same time.”[7]

The Pain of Digital Immigrants

Everyone seemed to have individual voicemail by 1999 because everyone still used phones for talking. Terminals began appearing in libraries and airports. TV-commercials hawked products and services all suddenly featuring a website, though some were bold enough to drop the “http://” and other pioneers were even foregoing the “www.” Kevin Poulsen, banned from the Internet as part of his parole conditions for a hacking conviction, desperately tried to recreate the experience his friends were having on-line by “reading the paper, listening to NPR, and watching Headline News all at the same time.”[7]

|

| One of the greatest of the archosaurs trying to survive. From Wired, February 1999. |

Those immigrants crossing the great divide into the digital world were, by 1999, struggling aloud. Many suffered from technological ailments like our ancestors used to suffer from the ague and dropsy. Columnist Stanley Bing believed cellphones took over their owners like parasites.[8] Editor Gary Wolf concluded that, by using email, “you are deciding to be tied to your computer for the rest of your life.” [9] Journalist Ira Flatow was forced to suffer through a long, loud cellphone call on the train from Connecticut to New York and wanted to start a “cell-safe car” movement, banishing cellphone users to the same alcoves as smokers.[10] Jerry Yang, a co-founder of Yahoo!, told readers that “If I’m on vacation, I don’t have cell phone, I don’t turn on my pager.”[11]

Ague. Dropsy. Pagers. Being off-line. People don’t get those ailments much anymore.

By 1999, Wired reported on global powerhouse Nokia, saying teenagers in Finland had stopped referring to mobile phones derisively as juppinalle, or “yuppie teddy bears,” and now called them kännykkä, or “extension of the hand.”[12]

Gary Wolf hit this hard, if slightly off-center, when he noted that the demands of email will grow more frequent “as computers shrink and become part of our clothes and our bodies. . .Turn off the flow,” Wolf said, “and people will go mad.”[13]

|

| From Wired's September 1999 issue |

And speaking of insanity, the dark side of the Web was surfacing by 1999. “We’re still enthusiastic about the Net,” said commentator Andrei Codrescu, “the way Walt Whitman was about trains and the telegraph. He thought they would unite us, make us all a community. He couldn’t predict the trains would go to a concentration camp.”[14] The first psychological delusions involving the Net were arriving in psychiatric offices, possibly a result of the 1995 movie The Net, which featured mayhem, floppy disks to die for, and identities erased from existence. Jeffrey Gregg of Gregg Microsystems—who might that be?—is exposed as a bad guy and gets his comeuppance.

By 1999, the ethos of Silicon Valley had swept across the country and seeped into the tech media. Author Po Bronson’s “Gen Equity” chronicled those “giving up their lives elsewhere to come here. They come,” he wrote, “believing that in no other place in the world right now can one person accomplish so much with talent, initiative, and a good idea.”[15] This was “superachieverland” where the “thrill of competition and the danger of losing” drove young people to practice “ultracapitalism.” This was Silicon Valley, 1999:

Get lean, get stripped down, live on nothing. Bare bones. Focus. Be a fighter. Ration yourself daily one Snickers. . .and one Dilbert cartoon. Forget about love that nourishes. Forget about food that satiates. Forget about long conversations that only get good in the middle of the night, when the third bottle of wine gets uncorked.”[16]

|

| Wired's July 1999 cover. |

|

| In 1999 the emphasis already was to flip, not build. |

The Coming of the Jurassic Period

Despite this frenzy in Silicon Valley, there was still a certain sense of calm pervading technology’s Triassic period. Not much was written about cyberattacks. We weren’t hacking everything in sight. No fake news. No gig economy. Not much on self-driving cars. No Uber to kick around. No deep analysis of emojis. No apps.

No selfies.

No selfies.

No pictures of food.

No drones. No cats riding vacuum cleaners. Little evangelism. Fewer Chiefs. Mobile, yes; social and mobile, no.

But the DNA of the apocalypse, the great giant that would rule the Jurassic Period was bubbling up.

Venture capitalist Jerry Colonna wrote a piece in which he described rushing out of a board meeting with three associates, jumping in a cab, and being stunned to watch all four investors remove Nokia 6160 cell phones from their pockets and begin talking to people hundreds of miles away—instead of to one another.[17] Visit a board room in 1999 and you might find executives talking not about marketing, but comparing the size of their phones—the first time grown men ever insisted that smaller was better. Motorola’s StarTAC was the reigning champion of tech-cool, but was under attack with every new competitive model.

|

| From Wired's June 1999 issue. We knew what we wanted. We just weren't sure how to ask for it. |

After all, we knew what we wanted, what technology’s Jurassic Era might look like, even if we were having trouble describing or building it. Bill Joy, the founder of Sun Microsystems, took a stab when he said, “What I want is a pocket-sized wireless 1- or 2-Mbps PDA plus phone, weighing 250 grams and connected to a pervasive digital wireless network.” And then, just to take some pressure off the future, he added, “I’m willing to accept lower baud rates in rural environments.”[18]

It seemed far too optimistic at the time. It turned out to be far, far too conservative.

Because nobody expects the next asteroid or volcanic eruption. It happens suddenly, wiping out three-quarters of life, and the new Era begins.

[15] Po Bronson, “Gen Equity,” Wired, Condé Nast Publications, July 1999, 113. This is drawn from Bronson’s book, The Nudist on the Late Shift.