A few weeks ago I tried to purchase a 1954 Saturday Evening Post on eBay. Unfortunately, I was also answering email, booking a trip, and trying to figure out why the cat was tormenting me. Needless to say, last week I received a Fortune magazine from 1952. Brilliant. Wrong magazine, wrong year.

And now that I think of it, I haven't seen the cat for a while, either.

There is a silver lining to my tale of woe, however: this particular edition of Fortune magazine turned out to be absolutely fascinating.

I wasn't alive in April 1952, but it wasn't exactly the Dark Ages, either. We now know the American Baby Boom was in full swing, life expectancy in the US was almost 69 years, Bill Clinton and George Bush were both well out of diapers, I Love Lucy (in one memorable evening) attracted 10 million viewers, and a killer fog descended on London resulting in the first use of the term "smog." That all feels pretty modern.

Though--and I write this with some surprise--there's nothing quite like a big, fat, colorful magazine from 1952 to remind us just how far we've really come. David Lowenthal said famously that the past is a foreign country; with that in mind, let me take you for a quick tour of America in 1952.

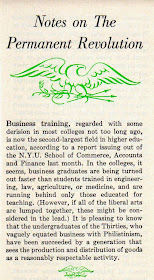

Image aside, while the country was in the midst of the Korean War, the economy had already come out of its WWII high. The theme of this 1952 Fortune was the desperate need to keep production chugging along by re-channeling wartime output from military to civilian markets. As you can see from the article above, there was plenty of national angst about that challenge--and (we'll learn later) no particular sense that the country was in the midst of a great, saving population explosion.

The important question addressed by the magazine was one we almost take for granted today: "Why do people buy?" Even though America was already home to a powerful consumer culture well in place by the 1920s, three decades later the consumer was still something of a mystery to American business. The caption reminding readers that "Consumers are not passive agents" is particularly surprising and a good reminder that the disciplines of selling and marketing were still in their formative years in 1952.

As if to provide counterpoint, however, one company demonstrated that it was ahead of the game. Alfred Sloan's General Motors featured three ads in Fortune, each spaced about ten pages apart, a kind of clinic in market segmentation and demand creation.

Ten pages later, here was luxury, gorgeous and regal--an extraordinary experience just to sit at the wheel. 20 million of your friends are dying to own one "if they felt it within their economic means." And it's in color.

Funny aside: There's a TV real estate show that gets watched around here from time to time, two brothers who tempt couples with new and renovated houses. Here's what these sneaky brothers do: They show the couple a house that is a fixer-upper, a real possibility but pretty basic. Then they show them a house that is exactly what they want but inevitably way beyond their budget. Then they show them an option right down the middle, one they almost always end up choosing.

I don't know why I thought of that.

Anyway, if Alfred Sloan was ahead of his peers with modern marketing, he still did not have modern roads.

Near as I can tell from this map--and the interstate highway system would become a project embraced by Dwight Eisenhower--south of about Delaware you may not have wanted to drive Alfred Sloan's Cadillac. In fact, it was clear to American industry in general that infrastructure was critical to the country's economic health.

I mentioned the Baby Boom above, and a couple of items in the Fortune 1952 edition were instructive. Just speaking for myself, I think of the "Boom" as a hockey-stick ride that began in 1946 and went non-stop for 15 years. Babies, new homes, more babies, air conditioners, lunchboxes, more babies and television sets, all moving up-and-to-the-right. Fortune was good enough to show us what the perfect Baby Boom family looked like in 1952.

The other fascinating thing Fortune reveals is that the Baby Boom wasn't exactly booming, at least in 1951. In fact, it was not obvious that a smart businessperson would place a big bet on there being anything like the greatest population bubble in American history.

It's a reminder that what we know to be history is rarely obvious and never a sure bet to those living it. In fact, how could a smart businessperson not predict a steady decline in consumer spending into the mid-1950s based on these trends?

And how did our 1952 businessman see himself? The ads throughout were generally consistent.

Where's the computer? I know. The desk looks terribly empty to me as well. And how was the "new breed" he was hiring into his business different from his own generation? They were, funny enough, coming out of business schools.

What office technology was at our 1952 businessman's disposal? Only the latest and best.

You might note, also, that every American woman in 1952 apparently had a 19-inch waist.

Tired of lugging those overhead projectors to your presentations? How about something with lifetime lubrication?

And, if you were smart enough to see the future, you might have put a bonus check into the stock of this company. Thomas Watson, Jr. took IBM over from his father in 1952, and four years later had one of his "business" machines playing checkers.

As for a real peek at technology, Fortune's April 1952 edition featured a fascinating article on the flavor industry. One of its conclusions could have saved a beloved American brand a ton of pain and suffering a few decades later: "Some products are so widely accepted that no variation is recognized as an improvement. Coca-Cola is an outstanding example." Another of Fortune's conclusions, I wonder, may have been influenced more by a growing sense of nationalism after WWII than by science: "Regional variations in taste, once fairly important, are rapidly disappearing."

And finally, the lessons of flavor and price as reported by Fortune: "There is considerable evidence to show that most people will pay a premium to get the flavor they prefer. . .A&P's medium priced coffee, Red Circle, outsells its less expense Eight O'Clock." Maybe, sixty two years later, we can call this "the Starbucks Rule"?

Our visit to 1952 ends with a note on media and fame. Not unlike today's Internet, television was staking its claim on the American consumer landscape, using celebrity (Mr. Television himself) to do so.

If you had to Google "Milton Berle," that's alright. He died in 2002 just after the Battle of Hastings. Such is the nature of celebrity. To make the point, here's an ad for Aqua Velva that stumped even me, old as I am, as I tried to figure out whom these 20 famous celebrity endorsers were.

Yes--I got Norman Rockwell and James Thurber. I can guess Cleveland and Doyle as famous spawn. I can take a stab at about three others. Then I'm done. (I'm not going to do all of your homework for you, but Dennis King was a Tony award-winning actor, George Biddle was a Philadelphia artist, and Conrad Nagel was a silent film star and matinee idol with three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Sophisticated celebrities in 1952, especially those who wanted to take "a young man's care" of their appearance, had almost all been born in the 19th century.)

It reminds you that striving for fame may be a kind of ruse, like a big bowl of lo mein that leaves you hungry a few decades later.

Anyway, that concludes my tour of 1952. It was certainly a different world, but different in the way your weird uncle is from your father; the strong resemblance is there, even if you don't understand all the inside jokes, and your mom makes him smoke outside and breaths a sigh of relief every time he goes home.

By the way, I'm still awaiting my correct edition of the Saturday Evening Post. You'll be happy to know, however, that the cat has reappeared--though I'm pretty sure she'll always think I'm Mickey the Dunce.